Understanding How Solar Panels Convert Sunlight into Electricity

Living with solar every day – whether it is a small off-grid cabin, a shaded suburban roof, or a portable power station you toss in the back of a truck – teaches you that solar is both simple and subtle. At the surface, sunlight hits a panel and lights turn on. Underneath, there is a carefully engineered chain of materials, voltages, and devices that turn scattered photons into steady power for fans, fridges, and battery banks.

This guide walks through that chain in plain language. We will look inside a solar cell, follow electricity as it moves through inverters and panels, and then zoom out to efficiencies, losses, and environmental trade-offs. Throughout, I will point to what national labs and agencies report, and balance that with practical, field-tested advice for residential and off-grid use.

Solar Electricity in Plain Terms

When people say “solar power,” they usually mean one of two things. Solar photovoltaic, often shortened to PV, uses solar panels to turn sunlight directly into electricity. Solar thermal uses the sun’s heat to warm water or drive turbines.

Because this guide focuses on solar lights, fans, portable storage, and off-grid essentials, we are mostly talking about PV.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the sunlight that hits Earth’s surface in roughly an hour and a half carries enough energy to meet humanity’s electricity demand for an entire year. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory says more solar energy falls on Earth in a single hour than the world uses in a year. That is why solar keeps showing up in every conversation about energy independence and climate.

The job of a solar panel is not to “make” energy out of nothing. It simply converts a tiny slice of that massive solar flow into electrical power you can store in a battery or feed into your home.

Inside a Solar Cell: How Light Becomes Electricity

A modern solar panel is an assembly of many solar cells. A single photovoltaic cell is a thin piece of semiconductor material, usually silicon, engineered to create an internal electric field. The U.S. Energy Information Administration describes a solar cell as a nonmechanical device that converts light directly into electricity.

Here is what happens when sunlight hits that cell.

Light from the sun arrives as tiny packets of energy called photons. When a photon hits the semiconductor, its energy can knock an electron loose inside the material. That creates a free electron and a “hole” where it came from. On its own, that would just be random motion. The clever part is the internal electric field built into the cell.

Manufacturers create that field by joining two slightly different types of silicon, often called p-type and n-type. One side has extra electrons; the other has extra positive “holes.” Where they meet, electrons and holes diffuse and leave behind a region with an electric field. When light frees new electrons near this region, that field pushes them in a preferred direction.

Once you attach metal contacts to the front and back of the cell and complete a circuit through some wiring, the pushed electrons flow around the circuit as direct current (DC). Each silicon cell only produces around half a volt, but many cells working together can generate useful power.

Government researchers note that individual cells are only about half an inch to a few inches across and typically produce about 1 to 2 watts on their own. That is why manufacturers connect so many of them into a single panel.

Why Silicon and What a Cell Is Made Of

Silicon dominates today’s solar market. As the Wikipedia entry on solar panels summarizes, crystalline silicon cells – both monocrystalline and polycrystalline – account for about ninety-five percent of modules, with thin-film technologies filling most of the remaining share.

A typical silicon cell includes several layers and features.

There is an n-type and a p-type silicon layer forming the junction and electric field. There are fine metal grid lines on the front to collect electrons, and a metal contact on the back. There is an anti-reflective coating on top so the cell absorbs more light instead of bouncing it away. Finally, there is a transparent cover and backing that protect the fragile silicon from moisture and mechanical damage.

All of these layers are thin, but they work together to trap light, free electrons, and guide them into a steady DC current.

From Cell to Panel to Array

One cell is a proof of concept. A panel is a practical device. Inside a panel, many cells are wired in series to raise voltage and in parallel to raise current. The cells are encapsulated in a clear material, sandwiched under tempered glass, and framed in aluminum. A junction box on the back brings the connections out to weatherproof connectors.

Commercial panels for homes are often rated between several hundred watts each under standard test conditions. The notes from Aurora Solar emphasize that these ratings are measured at about 1,000 watts of sunlight per square meter and around 77°F. Real roofs are hotter, dirtier, and usually not aimed perfectly at the sun, so there is a gap between that lab rating and what you see in your monitoring app. We will unpack that gap shortly.

When you mount multiple panels together, you get a solar array. A typical American home aiming to offset most of its electricity might use something like twenty to twenty-five panels, according to guidance summarized from EvoEnergy. Smaller off-grid cabins or portable systems might run happily on one to eight panels, depending on how modest the loads are.

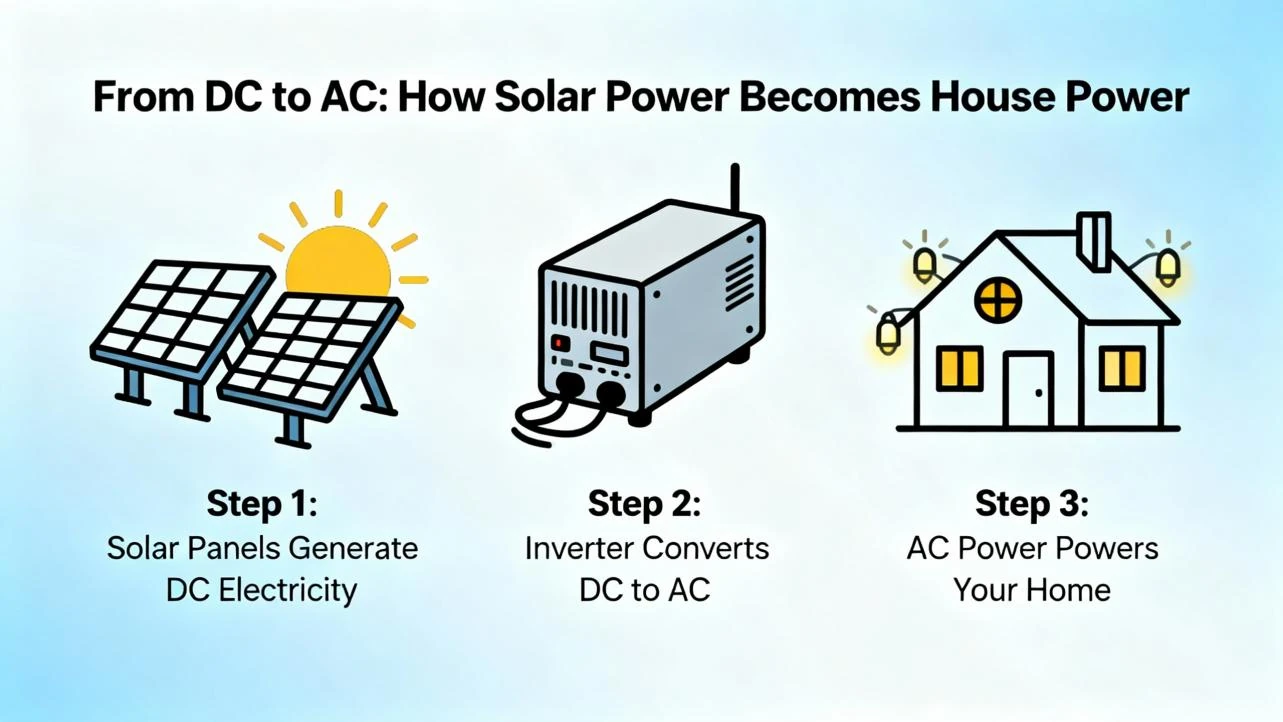

From DC to AC: How Solar Power Becomes House Power

So far, we only have DC electricity. Most household appliances, and the utility grid itself, run on alternating current (AC). The inverter is the bridge between those worlds.

According to resources from the U.S. Department of Energy and several residential solar providers, the basic flow in a PV system goes like this. Sunlight hits panels and becomes DC electricity. The DC flows through wiring to an inverter. The inverter converts DC to AC at the correct voltage and frequency for your home. From there, the AC goes through your main electrical panel, powers loads like lights and fans, and, if there is extra, it can go into a battery or out to the grid.

Types of Inverters and Why They Matter

In a simpler system, many panels are wired together into one or more strings that feed a single “string inverter” mounted near the electrical panel. The inverter sees the combined DC and turns it into AC.

More complex roofs, especially those with partial shading or multiple orientations, often use microinverters. In that design, each panel has its own small inverter on the back. Microinverters let each panel operate at its best point even if its neighbors are shaded, and they provide panel-level monitoring.

There are also power optimizers, which sit at each panel and condition the DC before sending it to a central inverter, and hybrid inverters that combine traditional inverter functions with battery management.

Aurora Solar notes that inverter efficiency is often in the mid- to high-nineties as a percentage, meaning most but not all of the DC power makes it through. That is one of several small losses that add up across a system.

For small portable and off-grid setups, this DC-to-AC conversion step matters even more. If you only charge cell phones, run LED lights, and power a DC fan, you can skip some inverter losses by running directly from DC outputs on a solar generator or charge controller. That is not a trick most grid-tied homeowners think about, but for a small cabin operating on a tight energy budget, reducing one more conversion step can make a noticeable difference. The reasoning is straightforward: when each conversion shaves off a few percent, cutting a step preserves more of the limited power your panels produce.

Grid-Tied, Hybrid, and Off-Grid Operation

Most residential PV systems in the United States stay connected to the utility grid. As Aurora Solar and the Energy Information Administration describe, this grid connection lets you import power at night or during bad weather and export surplus solar during sunny hours.

Under policies like net energy metering, surplus electricity you send to the grid earns credits that reduce your future bills. Some regions use bill credits, others pay cash at specific feed-in rates. Policy changes, such as the shift to new net metering rules in California, can affect how valuable those exports are over the life of a system.

Hybrid systems pair panels with batteries but stay grid-connected. They can store excess solar for evening use, ride through shorter outages, and participate in programs where utilities pay homeowners to share stored power as part of a “virtual power plant.” The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that energy storage deployment could multiply at least fivefold between 2020 and 2050, which is why this model is becoming more common.

True off-grid systems cut the cord entirely. In that case, your panels, batteries, and maybe a backup generator are your only sources of power. Every step of the energy chain, from sunlight to battery charging to inverter efficiency, becomes more critical, because there is no grid to lean on when you underestimate consumption or hit a cloudy week.

One subtle point that many introductory guides gloss over is that a grid-tied home with a battery is not automatically “off-grid.” Safety rules often require grid-tied inverters to shut down during a utility outage unless they are specifically certified to form an independent microgrid. That means resilience requires not just panels but also the right inverter and battery configuration, something to clarify early with your installer.

The Rest of the Hardware: Balance of System Components

Panels and inverters get most of the attention, but everything that is not a panel is grouped under “balance of system,” usually shortened to BOS. Aurora Solar and CertainTeed highlight several BOS elements that matter for safety and performance.

Mounting and racking hold panels in place on roofs, poles, or ground structures. Good racking is engineered for wind and snow loads and keeps panels at the intended tilt and spacing.

Wiring, connectors, and junction boxes carry DC and AC power around the system. Even though wiring losses in a well-designed system might be only a couple of percent, loose connections or undersized cables can create hot spots and safety hazards.

Disconnects, breakers, and fuses let you safely shut down and protect parts of the system during maintenance or faults. Modern codes also require rapid shutdown capabilities on roofs for firefighter safety.

Meters measure energy flow. For grid-tied systems, a bidirectional utility meter records both consumption and exports. Smart meters can report data in real time, which supports net metering and more precise billing.

Charge controllers manage the flow of power from panels into batteries in off-grid and hybrid systems.

Together, these BOS components are as important as the panels themselves. A well-designed BOS layout supports both performance and long-term reliability.

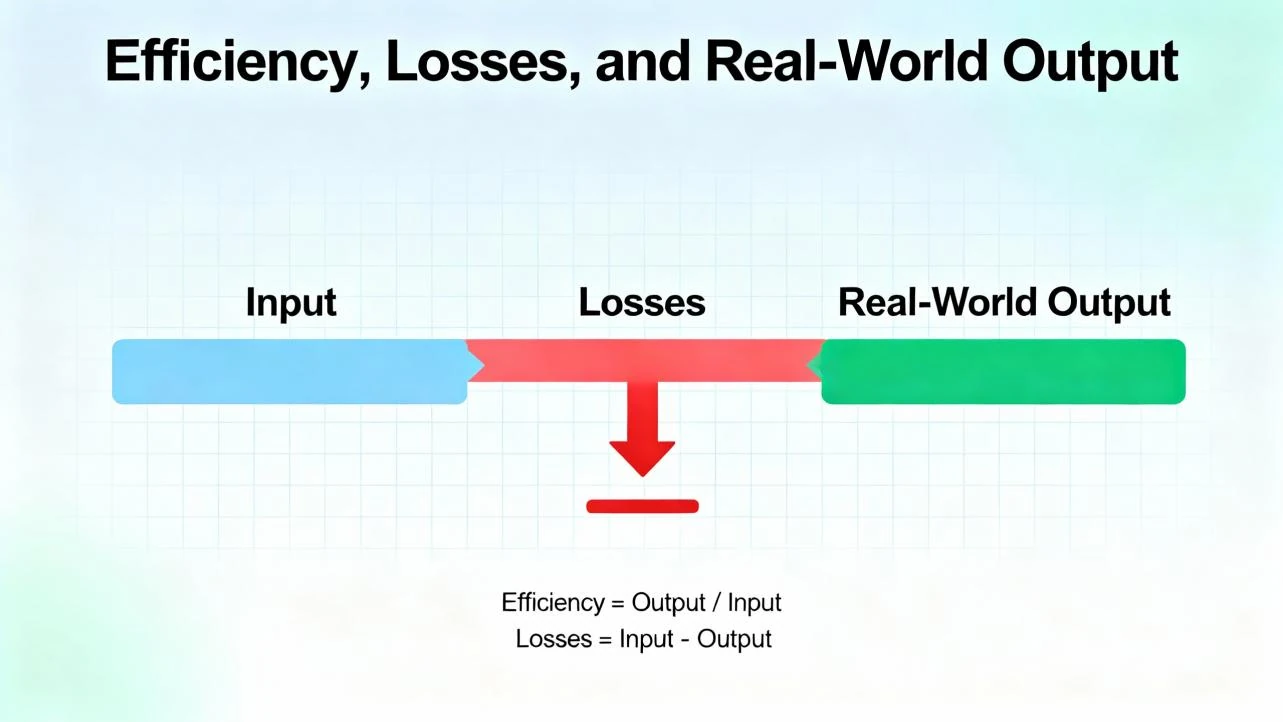

Efficiency, Losses, and Real-World Output

Manufacturers like to highlight module efficiency, the percentage of sunlight that a panel converts into electricity under lab conditions. According to Earth.Org and the Energy Information Administration, many commercially available panels convert around fifteen to twenty percent of incoming sunlight, with state-of-the-art modules now approaching about twenty-five percent.

However, the efficiency of your whole system is lower than the panel number alone. Aurora Solar and NREL describe a useful concept: the system derate factor. This combines several losses into one overall factor. In the U.S., the PVWatts tool from NREL uses a default derate around eighty-six percent. That means you multiply the ideal panel output by about 0.86 to estimate realistic system output under the same sunlight.

Where does that fourteen percent loss go? Some key contributors appear consistently in lab and field data.

Higher temperatures reduce output. Aurora Solar notes a typical loss of about half a percent of power for every degree Celsius above roughly 25°C, which is about 77°F. Roof-mounted panels often run well above that temperature on summer afternoons. If you translate that to Fahrenheit, it works out to roughly half a percent loss for every 1.8°F above that reference point. That provides a simple rule of thumb: a hot roof can easily shave ten percent or more off your peak power compared with a cool, breezy test bench.

Soiling such as dust, pollen, leaves, or light snow blocks sunlight. Aurora Solar uses a representative soiling factor around ninety-five percent, meaning about a five percent loss on average. In dusty or polluted regions, that number can be worse without regular cleaning.

Shading from chimneys, trees, or neighboring buildings can be very damaging if it falls on the wrong cells or strings. Smart modules with microinverters or optimizers help here by keeping shaded sections from dragging down entire strings.

Wiring and connection losses might cost around two percent. Inverter conversion losses add a few more percent, even with mid-nineties efficiency. Manufacturing tolerances cause “mismatch” between slightly different panels, adding more small losses.

Age-related degradation is another piece. The Aurora Solar and Earth.Org notes reference typical degradation on the order of about half a percent per year. Over a twenty-five to thirty year lifespan, that means a panel might still produce around eighty to ninety percent of its original power.

Here is one helpful way to put these pieces together, and it is an insight many homeowners do not hear up front. If a panel is rated at a certain wattage in the lab, and your system has a derate factor around eighty-six percent, then under the same sunlight your whole system will deliver only about eighty-six percent of that wattage. Layer on the fact that your roof is rarely at the perfect angle or temperature, and you begin to see why portable and rooftop systems often produce sixty to eighty percent of the advertised peak output in everyday conditions. This is not a flaw; it is just how real environments differ from ideal test benches.

Energy Payback and Lifetime

When people worry about whether solar is “worth it” environmentally, they often ask how long it takes a panel to generate as much energy as was used to make it. The Energy Information Administration reports that the energy payback time for PV systems is typically about one to four years. At the same time, PV systems often operate for thirty years or more.

That leads to another underappreciated point. If a system pays back its embodied energy in a few years and keeps running for several decades, then most of its lifetime electricity – easily well over eighty percent – comes at a net energy profit. Combine that with the Earth.Org finding that coal plants emit about twenty-five times and natural gas plants about ten times the lifecycle emissions of solar, and you get a clear picture: even after counting manufacturing and recycling, solar electricity is dramatically cleaner than fossil-based power.

Orientation, Climate, and Site-Specific Performance

The best hardware will underperform if it is pointed the wrong way, shaded, or installed in a poor climate for solar.

In the continental United States, Energy Department and installer guidance generally recommend facing panels south for maximum annual production. Palmetto’s step-by-step guide notes that the optimal tilt angle is often close to your latitude, which ranges from roughly the mid-twenties in southern Florida to just under fifty degrees in northern Minnesota.

However, real roofs have fixed pitches, dormers, vents, and other constraints. It is usually better to accept a slightly less-than-ideal angle on a structurally sound, unshaded area than to chase a theoretical perfect tilt that requires complicated structures or creates new shading.

Clouds and location matter as well. The Earth.Org brief emphasizes that solar is weather dependent, but it is not an all-or-nothing proposition. In cloudy conditions, panels might still produce ten to twenty-five percent of their rated power, according to data summarized from EvoEnergy. Even regions with relatively modest sunlight, such as the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, have solar resources comparable to countries like Germany, which has deployed a large amount of rooftop solar. The U.S. Department of Energy’s residential solar guidance points out that cost savings are still possible in those cooler, cloudier regions.

A less obvious but practical nuance comes from the temperature effect. Extremely sunny deserts offer abundant sunlight but can push panels to high operating temperatures, which reduces their efficiency. Cooler, clear-sky regions with decent sun can sometimes see panels operating closer to their nameplate output because they stay nearer that 77°F reference point and often benefit from more natural cleaning by rain. The physics is straightforward: the same irradiance delivers more electrical power when cell temperatures are lower. This is not a reason to avoid desert installations, which still perform very well, but it shows why “more sun” is not the only determinant of energy yield.

Shading analysis is another crucial step. Professional installers, as described by EcoFlow and others, start with a site assessment to check roof condition, orientation, and shading from trees or neighboring buildings. On off-grid land, that same assessment might happen with a handheld solar pathfinder or even careful observation through the seasons. A small amount of shade at the wrong time and place can do more harm than you might expect, especially on older string-inverter systems without panel-level electronics.

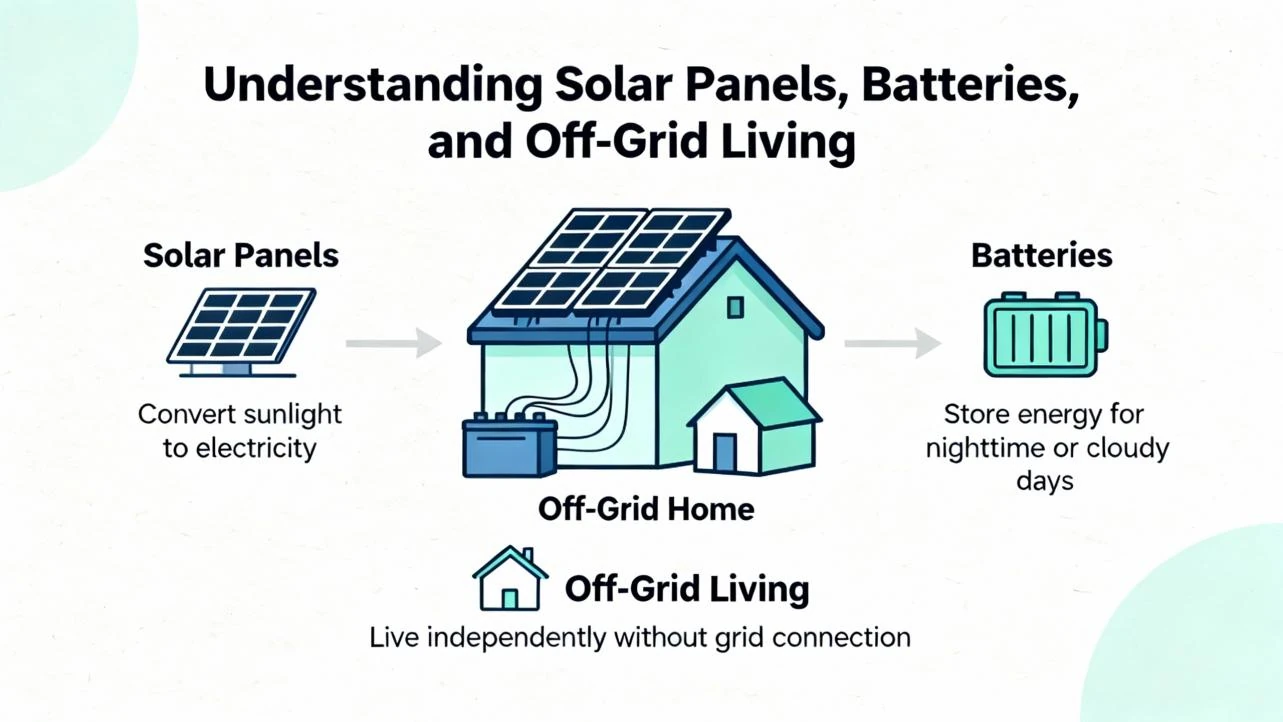

Solar Panels, Batteries, and Off-Grid Living

From a practical off-grid perspective, solar panels are only half the story. The other half sits in your batteries and your expectations.

Solar panels generate DC electricity when the sun is out. Batteries let you store that energy for evenings, rainy days, and unexpected usage spikes. Notes from Palmetto and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory describe how batteries are increasingly deployed both in homes and at utility scale, and how storage capacity is projected to grow dramatically in coming decades.

For a grid-tied home, batteries can reduce your evening grid draw, back up key circuits, and participate in incentive programs that reward you for sharing stored energy back to the grid during peak demand. For a fully off-grid cabin, batteries effectively define your energy “budget” between sun cycles.

Here is a practical way to think about it. Short outages emphasize the value of batteries and inverters; long outages or true off-grid living emphasize the value of panel area. During an eight-hour blackout on a sunny day, a modest battery and a grid-forming hybrid inverter can keep essentials like lights, fans, and a fridge running even if your panel array is not huge. Over a week of storms or in a remote homestead, the limiting factor becomes how much energy you can harvest on marginal days. In that scenario, more panel area – and fewer unnecessary loads – often does more for your resilience than simply adding more storage.

This difference explains why grid-tied backup systems sometimes size panels primarily to offset bills while sizing batteries for peak outages, while remote cabins often oversize the array relative to the battery bank to ensure recovery between cloudy spells. The logic is that solar panels are passive and durable, while batteries have finite cycle life and cost more per unit of stored energy than panels cost per unit of generated energy.

Portable battery power stations integrate panels, batteries, and inverters into one box with solar inputs on the outside. Under the hood, the physics is the same: photovoltaic modules still produce DC, charge an internal battery through a charge controller, and an inverter turns that stored DC into 120 volt AC output. Knowing the underlying process helps you interpret the specs, particularly the difference between panel wattage, battery capacity, and inverter rating.

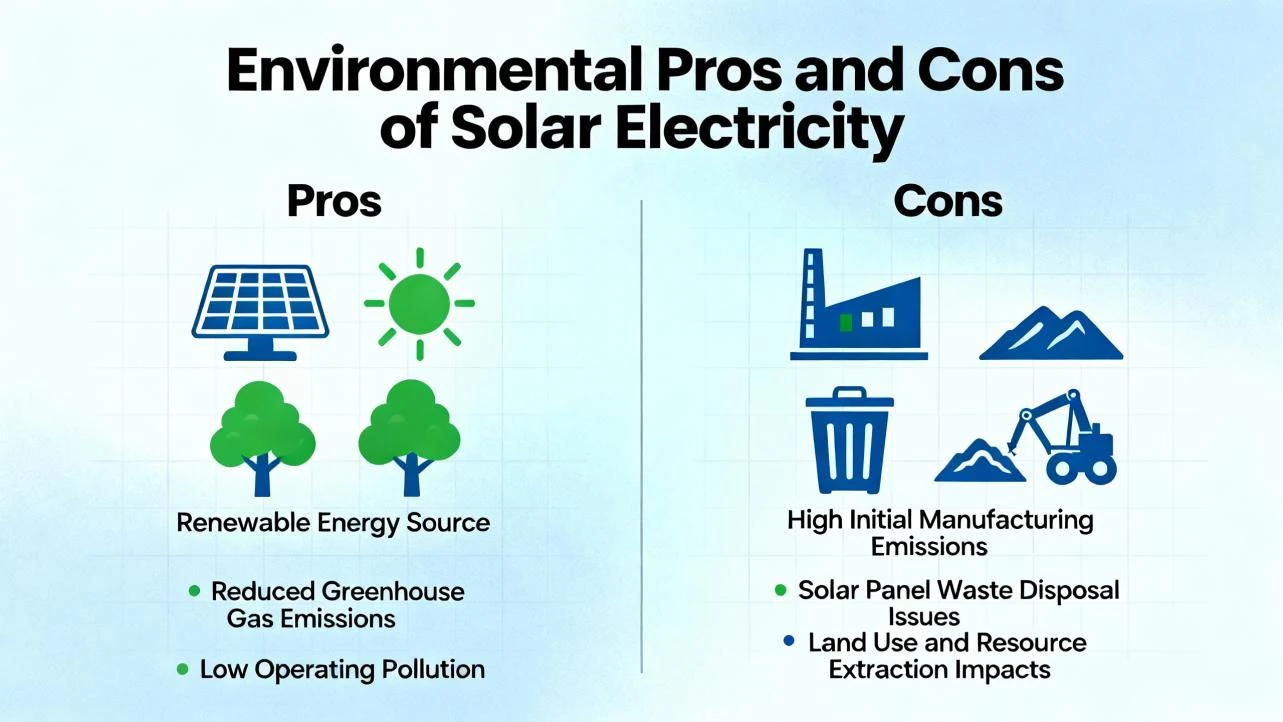

Environmental Pros and Cons of Solar Electricity

At the point of generation, solar PV systems do not emit air pollution or greenhouse gases. The U.S. Energy Information Administration points out that both PV and solar thermal technologies have minimal operational emissions, and Earth.Org emphasizes that even after including manufacturing emissions, solar’s lifecycle carbon footprint is far smaller than that of coal or natural gas. They report that coal plants emit about twenty-five times the lifecycle emissions of an equivalent solar installation, and natural gas plants emit about ten times as much.

However, upstream and downstream impacts still matter. Panels and balance-of-system hardware use energy-intensive materials such as metals and glass. Manufacturing involves hazardous chemicals and sometimes heavy metals. These must be handled carefully during production and at end-of-life.

Land use is another concern. Earth.Org cites an estimate that a solar power plant supplying electricity for about a thousand homes would require around thirty-two acres. Scaling that to meet all U.S. electricity needs could require nearly nineteen million acres, around 0.8 percent of the country’s land area. The Department of Energy suggests mitigating these impacts by prioritizing marginal land and integrating solar with agriculture or existing infrastructure.

There is also the issue of waste. The International Renewable Energy Agency projects that solar systems could generate up to seventy-eight million tonnes of waste by 2050 as early generations of panels reach end-of-life. The Energy Information Administration notes that end-of-life management for PV is an emerging focus, and that the Department of Energy is supporting efforts to recover and recycle materials from panels. Some states have already created laws that encourage or require PV recycling.

An important nuance here is where panels are installed. When solar replaces farmland or natural habitat with ground-mounted arrays, land-use impacts are more visible. When panels sit on existing rooftops, carports, or structures like barn roofs and shade pergolas, they often add very little incremental land impact. For off-grid homesteads, mounting panels on roofs or multi-use structures such as solar carports and equipment sheds can provide both electricity and shade without clearing new land. The reasoning is simple: reusing already disturbed or built surfaces concentrates infrastructure rather than spreading it over untouched areas.

Maintenance and noise are relatively minor environmental issues but worth mentioning. Enel and other sources point out that solar systems are quiet, with only cooling fans or inverters making modest sound. Maintenance is usually limited to periodic cleaning and occasional inspections, since panels can last twenty to thirty years or more with gradual efficiency loss.

Practical Guidance for Homeowners and Off-Grid DIYers

Whether you want to trim your utility bill or power an off-grid shop, the basic decision process follows similar steps.

First, understand your energy use. For a grid-connected home, your electricity bills show monthly kilowatt-hour consumption. For an off-grid cabin, lists of devices, their wattage, and how many hours per day you use them give a starting point. This matters because system size and cost hinge on how much energy you need to produce and store.

Next, evaluate your site. Professional installers, as described by EcoFlow and others, assess roof condition, structure, orientation, and shading before designing a system. If your roof is near the end of its life, it often makes sense to address that before adding panels. For ground mounts, consider soil conditions, snow loads, and access for occasional cleaning.

Then, think about configuration. A simple grid-tied system without batteries maximizes bill savings where net metering is strong. A hybrid system with batteries adds resilience and time-shifting but costs more. A fully off-grid system demands more design attention to panel area, battery capacity, backup generation, and load management.

Panel orientation and tilt matter, but perfection is not required. A south-facing array at a tilt near your latitude provides strong year-round performance, but east- and west-facing sections can be worthwhile, especially when time-of-use rates reward morning and evening production. Vertically mounted bifacial panels, which the Wikipedia summary notes have become popular at utility scale, can also capture light from both sides and shed snow more easily, but they are less common in residential settings.

Finally, plan for monitoring and maintenance. Modern inverters and apps, like those described by Palmetto, let you see how much electricity your panels generate and how much you draw from the grid or battery. Watching those flows over a few seasons often reveals inexpensive efficiency wins, such as shifting heavy loads into sunny hours or upgrading inefficient appliances.

On the maintenance side, the Aurora Solar data suggest that soiling might cost you around five percent of output on average, but that figure is very site-specific. In regions with frequent rain and little dust, panels can stay relatively clean. In dusty areas or near tree pollen, occasional cleaning can reclaim noticeable power. One practical observation from both homeowners and designers is that sometimes it is more economical to slightly oversize the array than to schedule frequent professional cleanings, except in extreme soiling environments. The reasoning is that a modest increase in panel area permanently boosts output, while cleaning costs recur over time. That said, safety on roofs comes first; if you cannot safely access your array, factor the cost of professional maintenance into your plans.

Pros and Cons at a Glance

The research notes support a balanced picture of solar electricity, with clear benefits and genuine trade-offs. The table below summarizes several key aspects.

| Aspect | Upside | Trade-off |

|---|---|---|

| Emissions and climate | Very low operational emissions; lifecycle emissions far below coal and natural gas; helps decarbonize grids and off-grid systems. | Manufacturing and disposal involve energy use and hazardous materials that require careful management. |

| Resource and scalability | Sunlight is abundant, renewable, and available almost everywhere; one to two hours of global sunlight could meet annual demand. | Utility-scale systems require land; estimates suggest tens of acres per thousand homes and millions of acres for national-scale supply. |

| Economics | Panel and system costs have fallen dramatically; agencies like the International Energy Agency describe solar as one of the cheapest sources of new electricity. Residential systems can often pay back in around six to ten years. | Upfront costs remain significant, especially when including batteries; policy changes in net metering and incentives affect payback. |

| Reliability and resilience | Systems have long lifetimes, often twenty-five to thirty years; panels are static devices with minimal moving parts. Batteries and hybrid systems can provide backup during outages. | Output varies with weather, season, and shading; off-grid systems require careful design to match loads, storage, and array size. |

| Maintenance and lifecycle | Routine maintenance is relatively light, mainly inspections and occasional cleaning; maturing recycling programs can recover materials from retired panels. | Without robust recycling and clear end-of-life policies, projected panel waste by mid-century could be substantial and must be managed proactively. |

Short FAQ

Do solar panels work on cloudy days?

Yes. Panels still produce electricity under cloudy or overcast skies, but at reduced output. Field data summarized by EvoEnergy and others suggest production might drop to roughly ten to twenty-five percent of rated power depending on cloud thickness. Over a year, even relatively cloudy regions can generate meaningful energy, especially with well-sized arrays.

How long do solar panels last?

Several sources, including Earth.Org and federal energy agencies, report that modern panels are typically warranted for about twenty-five years and often continue producing for around three decades with gradual performance decline. Average degradation rates on the order of about half a percent per year mean that after twenty-five years, many panels still deliver most of their original power.

Can solar power my home during a grid outage?

Grid-tied systems without batteries usually shut down during an outage to protect line workers, even if the sun is shining. To have power during blackouts, you need a system designed for backup, usually with a hybrid inverter and batteries that can operate safely when the grid is down. Off-grid systems are built for this from the start, but they require more careful design and right-sizing.

Closing Thoughts

Understanding how solar panels turn sunlight into electricity makes it easier to design systems that actually fit your life, not just your roof. When you recognize that a panel is a precise sandwich of silicon, glass, and metal, that an inverter is the translator between DC and AC, and that real-world losses and weather matter as much as datasheets, you can ask better questions and make more confident choices.

Whether you are wiring a single panel to keep a battery-powered fan running in a shed or working with an installer on a whole-home system, the principles are the same. Start from your actual needs, respect the physics, and let the sun do the quiet, steady work it has been doing for billions of years.

References

- https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/benefits-residential-solar-electricity

- https://www.nrel.gov/research/re-solar

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_panel

- https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/solar/photovoltaics-and-electricity.php

- https://www.raiuniversity.edu/wp-content/uploads/naac/ssr/3.4.4/3.4.4/33.pdf

- https://uwf.edu/hmcse/departments/earth-and-environmental-sciences/research/student-research-blog/the-benefits-to-solar-energy.html

- https://earth.org/what-are-the-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-solar-energy/

- https://www.netzero.gov.au/turning-sunlight-electricity-how-does-solar-power-work

- https://www.lgcypower.com/how-do-solar-panels-turn-sunlight-into-electricity/

- https://lucent-energy.com/how-solar-panels-convert-light-into-electricity/